|

|

In this section, I share my most beautiful hikes. SEE THE LIST OF HIKES. |

|

Return to the story of the previous day. September 14, 2019: second day. Hike to the rocks of the mottets. A beautiful morningI slept in dotted lines that night. Moments of awakening which I cannot estimate the duration alternated with moments of sleep. The next morning, my heart had found a normal rhythm. Standing from the early day, I went out immediately to enjoy the sunrise. The sky was pure, clear. The dawn was announced in pastel shades. The sun still shyly illuminated the immense circus of the Mer de Glace, from the Grandes Jorasses to the Mont Blanc. I take the only photo of the day, still because of discharged batteries, before going inside.  The Belvedere of the Charpoua refuge offers a magnificent panorama ranging from the Géant tooth to the Mont Blanc. A climber who wanted to make a path in the Drus had slept on the ground. He had already left, leaving his mattress. Another abandoned mattress testified to a second night start. I tidy up the mattresses to clear the kitchen benches. Pascal being lifted, We were able to have breakfast with a few sachets of soluble coffee and rice rice cakes that, like each time, We found it excellent, as we had the impression of having an empty bag instead of the stomach. The balcony trail.

The Charpoua refuge is a dead end, except for mountaineers, for whom it is a springboard for the ascent of the Drus.

We therefore left by taking the same path as the day before,

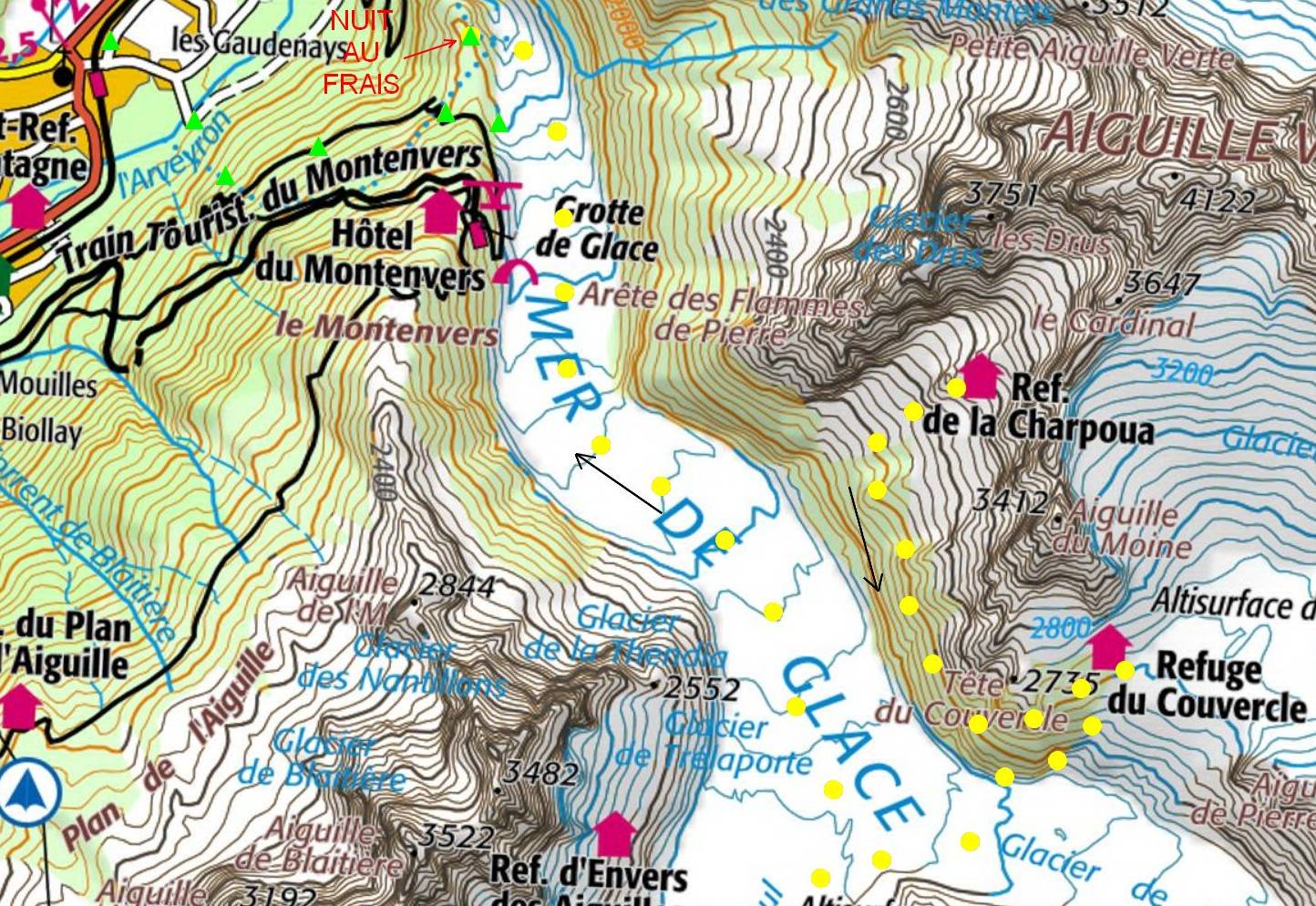

Descending a large number of scales to find the bifurcation leading either to the sea of ice or to the refuge of the cover.

But, after a while, no brand of paint, no cairn, were no longer visible. We stopped. Were we already lost? No because,

Looking carefully in the distance, I saw discreet and old brands on a rock.

However, Pascal did not remember having passed there the day before. Too bad, we would see! Shortly after, the mystery is clearing up:

We had just borrowed part of the balcony path, normally inaccessible since the Mer de Glace melted too much to allow to go up to the scales that lead there.

We arrived shortly after for bifurcation.  The itinerary of the second and third days, from the Charpoua to the Bois. Contemplate the sublime.The view was sublime. The great Jorasses, the Géant's tooth, the seracs of the Géant glacier, seen more closely than the day before, were even more impressed ; A break allowed us to enjoy it longer. The Triolet needle was also guessed on the left. A walker, with whom we had discussed the day before at the refuge, joined us. I hadn't seen him so far, but he shouldn't be far behind us. He taught us that he was not going to the Couvercle, our paths would separate there: He would descend to the Mer de Glace through the scales by which we had come. We watched him move away, then, after taking us one last time from the majesty of the place, we took the path of the refuge. It is a less difficult path than that leading to the Charpoua. Crossing thirst.A long and easy crossing leads, at 2,679 meters above sea level, to the new refuge of the Couvercle. Construction is visible from a distance, and, like many recent shelters, we guess, well before getting there, a stone building hides the parasols, tables and benches of a terrace. A modern refuge is also a refreshment bar and an inn. His silver returns come more from food, breakfast, drinks taken on the terrace in the afternoon, and from the evening meal, than from the berths. The traditional refuge has turned into a hotel-cafe-restaurant. For a mountaineer soul to loose the mountain for itself, and not for what you drink or eat, appreciate a refuge, it must go when it is no longer kept, generally from the end september. There is then nothing to eat, but a door is always open to allow practitioners to enter it for the night. In the mountains, one night in cooling can be fatal, it has been in the past for too many mountaineers ; also, in these moments of distress, the refuge really deserves its name. The day before, that of the Charpoua was no longer kept, and today, approaching, we did not see anyone outside of it. However, the parasols had not yet returned, and the tables seemed to wait for customers. It was strange. The deserted refreshment bar.The goalkeeper looked very busy inside. Pascal adventped there, visiting the places, the dining room, the dormitories. I heard him chatting with the goalkeeper, who explained to him that he was preparing his departure for the next day. So it was here the last day and the last night guarded of the season. Attracted by a tap that I saw above a sink from the entrance hall, I decided to remove my shoes and penetrate further. Serious error! Because, while heading to the water point to fill my gourd, I heard behind my back, the goalkeeper reproach me, in a tone of bad mood, for having entered with my bag and my ice ax. He feared that I hang the wooden furniture, or the walls. I reassured him, and he let me finish. The gourd full, I hastened to come out. Pascal joined me. He had seen the chichon lying around in a corner, which I had not even felt. Abandoning the goalkeeper in his storage, we put each other again to go to the old refuge, a few tens of meters. The stone cover.

Seeing it, we immediately got into it why it is called the Couvercle refuge.  The Droites, 4000m, and the former Couvercle refuge. Photo taken by Pascal, published with his kind permission. Find it here on his blog. Built in a natural shelter formed by the space between a gigantic stone, fallen there by chance, and a soil raised by the hand of man, it undoubtedly benefited from an excellent protected location of the falls of stones, of the avalanches and wind. The low space available did not prevent the interior, recently renovated, from being warm, welcoming, and surprisingly comfortable. But the place is small, hence the new neighboring building, more in accordance with the current standards of mountain refuges, and adapted to increased attendance with the development of mountaineering and hiking. From the door of the old refuge, an easy climbing step brought us to the stone which forms the famous couvercle. It is almost horizontal. You can sit there and put your bag near you, it is not likely to slide, which is practical to have something to make a small meal while contemplating again, but even closer, the big Jorasses and The Géant's tooth in front of us and, on the opposite side, towards the north, the glacier and the Talèfre garden, which Pascal described me. But, as soon as we arrived, we had to leave for us already since, being at the place of the route furthest from the woods, from where we had left the day before, a long path was still to be traveled to return to our starting point. The mechanical descent.We had to put our feet on the Mer de Glace first thanks to the most southern access scales to the Couvercle. We didn't have time to go to Talèfre garden and come back to it. So we started on the way for a long, but beautiful and easy descent to the first scales. I started to feel a slight fatigue. Was it due to the repetition of the walk during this descent? I do not know. In any case, I was relieved to start the scales. Borrowing them from the descent was fun, and with the lanyard, there was no danger. Connected to the harness which surrounded my buttocks by a shock absorber formed by a flat strap sewn, it had two elastic straps each ended with a carabiner. By being provided by a carabiner that I had placed above me, I put the second carabiner around a downstream bar from the ladder, then I released the upstream carabiner, and I started again to progress down. I was constantly assured. The scales succeeded each other. We had a repetitive rhythm, almost mechanical, which we kept until the last hectometers of vertical cliff. A delicate step.It was then that we saw a group go up to us. Alone on the route, we had hitherto had no problems of crossing. Our luck had abandoned us. It was necessary to manage the crossing of two groups progressing in the opposite direction in the wall. By an unfortunate coincidence, we were in a part of the cliff where there was no more scale, probably carried away by a fall of rocks, but a rope and iron steps sealed in the rock. The passage was delicate. I stopped on a step formed by the rock in a fireplace, While Pascal, below, managed to descend a little, before stopping too. I could not reach him without taking a risk. The first of the upright group arrived at Pascal level. How could we meet? In support of this walk, I collaborated against the wall. No longer risking anything, I observed my environment. There was a steel walk located in the cliff on my right, up to my shoulders. It came to me an idea: if only one could use this solid point as a ring. But yes ! Eurêka! I asked the group to wait, the time I checked the validity of my idea, telling them that if the test that I was preparing to do was conclusive, we could all cross this passage exposed by being insured. I took a step on the right, I reached out, finger of the open carabiner, And I placed it around one of the two horizontal bars of the walking, between the two plates which were welded there. Yes, the space between the two plates was sufficient for the carabiner to pass. I explained to the group, speaking strongly and clearly so that my explanation was heard, where and how to place one of their carabiners on this walk to make sure, then I wedged myself against the rock and let them pass. Finally, I used it myself and ended up getting out, insured by my lanyard, then by the rope, of this delicate step. I had made a great fright! In the mountains, a simple bad luck can cause a chain of problems that lead to a drama: a slide step, a too short rope, a slippage on ice, a crossing without the possibility of securing, ... Tantale torture.A few more scales, a rope and a little jump, and we found the glacier we had left the day before. The sun, relentless at this hour of the day, radiated intensely. I was hot and thirsty. Obviously, it was paradoxical, because we were on a large amount of water. We were walking on solid water, a gigantic ice cube. But that didn't help us much. I told Pascal, who assured me that nothing was easier than finding water quickly. I followed it and, in fact, we were soon in front of one of the mills who traversed the glacier. We filled our gourdes and logs all our drunk, which swept our fatigue and gave us a smile. Jaws of the Mer de Glace.I then asked my friend about his intentions. It seemed to me that the time had come to join the Montenvers. He had another desire, that of getting closer to the giant's glacier and the access ladders to the shark refuge. For this, we had to go up the glacier by heading west. We first got closer to the foot of the giant needle, when an unforeseen obstacle appeared to us, a mill at the foot of a mound of vertical ice cream, wide enough to be difficult to step up, but not enough for us turn back. Pascal won the river to find the easiest place to cross, stopped, planted his ice ax far and high on the hill, and reached, pulling on the ice ax, climbing there. My turn ! I hesitated, I tried once, twice, without success. He then came an idea. I come back back, where I spotted a stone in the middle of the mill. I thought I would support it to jump on the other side, the height being weaker here. Badly took me, because I slipped by placing a shoe on the stone. My foot was a short time in ice water. I passed, and raised him immediately, but it was already too late. Water at barely positive temperature had entered the shoe. Even if it was waterproof, this waterproofing was not total. My sock was now wet. But, as I still managed to go to the other side of the mill, I joined Pascal. He reproached me for not having followed him. I was not acrobat enough, and I started to be invaded by weariness that limited my desire to make physical exploits. We took our way by forcing towards the other side of the glacier, but our progress, easy at first when we had set foot on the sea, became increasingly difficult. We were in a part of the hilly glacier and covered with stones that slowed us down and forced me to look at where I was walking.  What have fun in the middle of these unstable scree, in the background the seracs and Géant glacier (upper part of the Mer de Glace). Photo taken by Pascal, published with his kind permission. Find it here on his blog. Pascal took more and more in advance, and, forced to stop regularly to raise my eyes and look for it, I could not catch him. The hour was running. Pascal became worried. We no longer had time to follow his project. So he finally decided to return to the Montenvers. A too late turnover.Too bad, we would not see the giant's seracs closely, but I was relieved. It was too much for one day. We went back down to the Praz. The walk quickly became easy on an almost flat terrain, but the Montenvers was still far away. The sun was already lower on the horizon, the brightness, less strong than on the lid, had already decreased well. It was time to go back. We were walking quickly while staying right on the sea of ââice, so that after a while we saw the numerous junction scales with the Montenvers platform. Alone, I would have returned by the Montenvers, and not by the motets, remembering the mishap that the refreshment waitress had counted to us, it seemed safer. Do we not say that prudence is a mother of security? I asked Pascal. He wanted to join the end of the glacier, then the Mottets, and finally the Bois. It did not enthuse me, I was aware that there was a risk, and I felt that Pascal was too. Probably he had to say to himself that we should find the refreshment of the refreshment bar before night while walking quickly, and that, having already taken this same path to go, we should find it on the return. Don Quixote and his mill.Going down again, we saw in the distance the tourist cave, its ski lift, the stairs that lead there, and the white canvases extended on the ice to delay the cast iron by reflecting the rays of the sun. To go to the Montenvers or to the Mottets, we had to cross the mill in the other way that we had a little trouble going through it. We looked for the best place for this. Pascal spotted what seemed to him the least steep passage, because, wanting to walk quickly, we had not put any crampons on our shoes. It was not necessary, because, on the one hand the ice was not pure, but encrusted with small fragments of rock which hung our soles, and, on the other hand, it was melted on the surface by the heat of the sun . But the carriage of the sun quickly advanced in its race, And this surface was now resolidified by forming a smooth and slippery film. Pascal was not confident. He decided to stop to put the crampons. I felt comfortable, I hadn't gathered once, I trusted my Vibram soles. Not listening to it, I stunned towards the side, in order to descend to the edge of the watercourse by making an S curve to reduce the slope. I had barely made a few meters since Pascal challenged me. He thought I was imprudent, and asked me to give up. After all, perhaps he was right, it would be silly to take unnecessary risks. I turned around, I joined him and I took my crampons out of the bag. These mini crampons are practical, easy to put, but they have no spikes at the front. You cannot use it either to climb a vertical ice wall, or to walk on rocks, because they are thinner and more fragile than real crampons. They are perfect for walking on soft sloping ice. The time I put them, Pascal was already at the bottom. He crossed the mill without problem. I looked at him carefully before following him. On the other side of the mill was a small hill that had to be climbed, but it turned out to be easy. Don Quixote and Sancho Panza had passed on the other side of the mill. The Mer shows its tongue. The final tongue of the glacier. Photo taken by Pascal, published with his kind permission. Find it here on his blog. We could remove our crampons. But these necessary maneuvers still took us time. The brightness fell. The glacier was no longer lit by the sun at all. The coming walk was still long. To take up the route to go in the opposite direction, we had to fall back on our right, against the eastern slope of the Mer de Glace, where the passage we had easily found the day before, then after having crossed A large mound made of a mixture of scree, earth, pebbles and ice, cross to the west to find the Mottets path. On this rugged terrain, we were walking difficult, but we were passing by this difficulty by pressing ourselves, because twilight began to fall. Finally, while I was very tired of this long day and the efforts to be concentrated by walking quickly on chaotic terrain, we saw a three -meter -high mast whose base was anchored in a large rock. We should now finally leave the glacier to go up by an easy path to the coveted refreshment bar. Swallowed by darkness.It was almost night. We no longer saw enough where the path was precisely. There was indeed a stick, but no mark of paint, neither on the rocks, nor on the surrounding trees; Where was the way to the way? We took out our front lamps from our bags and lit them. It is by leaving at this precise moment that we made an error in the serious consequences. The error is human.Instead of following the riding path, which we did not see when he was before our eyes, we continued below. Then, having advanced too much, we sought to go up. It seemed easy at first, but soon our route became more abrupt. There were more and more brush. They stretched us, while increasingly large rocks made us obstruct. Finally, Pascal, who left forward, returned to me, announcing that he had met an insurmountable rocky barrier above. Convinced of having made a bad choice when we were at the mast, we turned around and set out in search of it. The night was not yet total. The low residual light of twilight allowed us to join him, but this attempt, however, took us a little time. We stayed near the mast for a moment, hesitating on the direction to follow, without seeing any material clue of the location of the path. Thinking that we had gone up the slope too early, we left on what we still believed, but wrongly, being the path, continuing longer on the same level curve. This is how, to our surprise, we came over to a clearing at the entrance of a small tunnel. I thought we were saved. |

CommentsThere is no comment yet. Be the first to write one!

|

|

|